On January 21, President Barack Obama will take personal responsibility for the wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan launched under President Bush. The Afghan-Pakistan war is uniquely Democratic in origin, however. Since John Kerry's 2004 campaign, hawkish Democratic security and political consultants have asserted that Afghanistan is a good and necessary war in comparison with Iraq which they label a diversionary one. This argument has allowed Democrats to be critical of the Iraq War without diminishing their standing as hawks who will employ force to hunt down Al Qaeda. As a result, the rank-and-file base of the Democratic Party, and public opinion in general, remains divided and confused over Afghanistan. As a result, opponents of the Afghanistan escalation remain at the margins politically for now, although backed by a healthy public skepticism given the Iraq experience.

Back on July 14, I wrote "Chasing Needles By Burning Haystacks" for the Huffington Post, a criticism of Obama's Iraq and Afghanistan proposals. In other writings for The Nation, I have been critical of the decision by liberal Democratic donors in 2008 to defund and shut down an independent media campaign that would have carried telelvision and radio messages against "McCain's wars." Now that they are becoming Obama's wars, the challenge will be more difficult, since so many millions of Americans, myself included, want our new president to succeed, restore hope, and launch a new New Deal at home, not be distracted by a quagmire abroad.

The war in Iraq already is fading from public view, although more than 140, 000 American troops remain stationed there. The major television networks have withdrawn. US casualties are far fewer than in traffic accidents on American streets. Iraqi violence is down as well, with 8,955 civilian deaths in 2008 compared to 51,894 in the bloodiest years of 2006-2007. The shift is towards a low-visibility counterinsurgency war like those that ravaged Central America in the 1970s.

The conditions for a massive social movement against the Iraq War are ebbing, for now, unless large-scale fighting suddenly resumes or President Obama unexpectedly caves in to the Pentagon and blatantly breaks his promise to withdraw combat troops in 16 months and all troops by 2011.

That makes Afghanistan the growing focal point for public debate over what counterinsurgency gurus call "the long war" against Islamic jihad.

In everyday language, Obama's proposals for Afghanistan and Pakistan can be described as either out of the frying pan and into the fire, or attacking needles by burning down haystacks.

The Pentagon paradigm is to defeat al-Qaeda militarily while refusing to address, and thereby worsening, the dire conditions that gave rise to the Taliban and al-Qaeda operatives in the first place. Ahmed Rashid's new Descent into Chaos [Viking, 2008] provides a horrific portrait of Afghanistan in careful prose based on reputable sources.

It is estimated by RAND that $100 per capita is the minimum required to stabilize a country evolving out of war. Bosnia received $679 per capita, Kosovo $526, while Afghanistan received $57 per capita in the key years, 2001-2003;

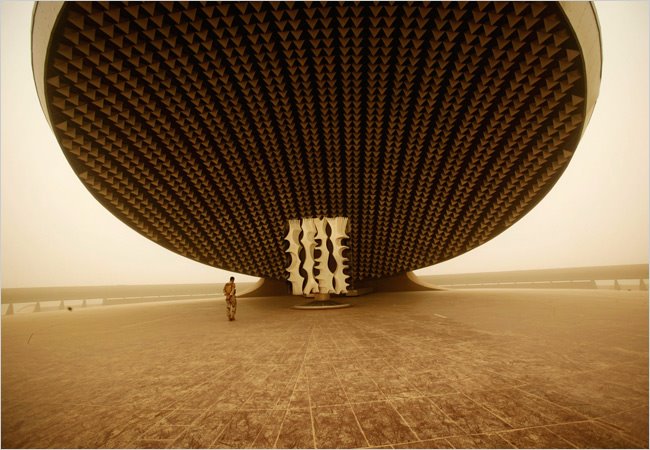

- When the US installed the Hamid Karzai government, Afghanistan ranked 172nd out of 178 nations on the United Nation's Human Development Index, having the highest rate of infant mortality in the world, a life expectancy rate of 44-45 years, and the youngest population of any country; in 2005 95 percent of Kabul's residents were living without electrical power.

- Seven hundred civilians were killed in the first five months of 2008 alone, according to the United Nations.

Despite some gains in media and currency reform, plus a modest increase in children in school, this was the path of least reconstruction.

And despite media images of Afghan democracy that made loya jirga tribal gatherings appear to be the birth of participatory democracy, a warlord state was entrenched by the CIA. The government is "shot through with corruption and graft", from the police to the presidential family, writes Dexter Filkins in the New York Times. [Jan. 2, 2009]

There are some 36,000 US troops stretched across Afghanistan, another 17,500 under NATO command, and 18,000 in counterinsurgency and training roles [New York Times, July 14]. It costs the Pentagon $2 billion per month to support the American troops.

The enlarged American forces are likely to "squeeze the Taliban first". [New York Times, 12-24-08]. The target will be the support networks of the Taliban which are embedded in the vast tribal lands of Pashtun civilians, which stretch from southern Afghanistan into Pakistan. The enlarged American forces are likely to "squeeze the Taliban first". [New York Times, 12-24-08].

Even Afghanistan's client president, Hamid Karzai, complains of extra-judicial killings and civilian casualties from the American air war, a pattern of repression and suffering which will only worsen with more American troops pouring into combat zones.

Meanwhile, the war in Pakistan and other Central Asian countries will expand as the additional US troops seek to recover supply lines closed by recent Taliban attacks. [No one comments that the Pentagon is carrying out precisely what it accuses the Taliban of doing, using Pakistan as a supply and staging area for its forces in Afghanistan. Eighty percent of those supplies flow through Pakistan, according to the New York Times, Dec. 31, 2008]

According to Rashid, "Afghanistan is not going to be able to pay for its own army for many years to come -- perhaps never."

As of 2006, Afghanistan's economy still rested on producing 90 percent of the world's opium, an eerie narco-state parallel with the US counterinsurgency in Colombia from where most of America's supply of cocaine originates.

Afghanistan is an unstable police state. By 2005, the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission cited 800 cases of detainee abuse at some thirty U.S. firebases. "The CIA operates its own secret detention centers, which were off limits to the US military." Ghost prisoners, known as Persons Under Control [PUCs] are held permanently without any public records of their existence. Warlords operate their own prisons with "unprecedented abuse, torture, and death of Taliban prisoners." And as the US lowered the number of prisoners at Guantanamo, it increased the numbers held at Bagram, near Kabul. As of January, 2008, there were 630 incarcerated at Bagram, "including some who had been there for five years and whom the ICRC had still not been given access to." After weeks of hunger strikes about detention conditions, the Taliban recently orchestrated a jailbreak of hundreds of Afghanis from the Kandahar prison, an inside job.

As in Iraq, the US contracted for police training in Afghanistan with DynCorp International; between 2003 and 2005, the US spent $860 million to train 40,000 Afghan police, "but the results were totally useless" according to Rashid. Even Richard Holbrooke described the DynCorp training program as "an appalling joke...a complete shambles."

When the Taliban government was overthrown, the US installed a Westernized Pashtun, Hamid Karzai, a former lobbyist for Unocal, who had been out of the country during the jihad against the Soviet Union. But the Pashtun tribes themselves were violently displaced from power for the first time in 300 years. They remain by far the largest Afghan minority at 42 percent of the population, heavily concentrated in Kandahar and the southern provinces and across the federally-administered tribal areas in western Pakistan. These are the areas that the Pentagon, the New York Times, and Barack Obama [like John Kerry before him] designate as the central battlefront of the war on terrorism.

The question is not simply a moral one, but whether the expanding war in Afghanistan and Pakistan, fueled by troop transfers from Iraq, is winnable, and in what sense?

Transferring an additional 20, 000 American troops from Iraq to Afghanistan, which Obama proposes, is symbolic, a step on the treadmill of escalation. The American troop level will be pushed to 58,000, in addition to 30,000 other foreign troops. Obama may be proposing an escalation simply in order not to lose, a pattern well-documented in Daniel Ellsberg's history of the Vietnam War.

The questionable premise of the coming escalation is that military success must precede any political solution. "What we need are more troops in Afghanistan because we need security, and eventually we will get a strategy", says a former Special Forces officer now with the think tank Center for a New American Security. [Dec. 23, 2008] But it could deepen the quagmire and turn more Afghans against Obama and the US as well.

In Pakistan, the Pentagon has fostered the ascension of a new Pakistani general, Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, whose background includes training at Fort Benning and Fort Leavenworth. An unnamed US military official praises Kayani "for embracing new counterinsurgency training and tactics that could be more effective in countering militants in the country's tribal areas. [New York Times, Jan. 7. 2008] Over $400 million is being spent to recruit a "frontier corps" of to "turn local tribes against militants" [New York Times, Mar. 4, 2008] CIA and Special Forces operatives already have invaded Pakistan to set up a secret base from which to hunt Osama bin Laden "before Mr. Bush leaves office" as well as fighting al Qaeda and the Taliban on the ground and from pilotless Predator drones. [New York Times, Feb. 22, 2008].

This constitutes another preventive war by the United States, this one in violation of Pakistan's sovereignty and the overwhelming sentiment of Pakistan's people. On the Afghan front, the Taliban will be able to retreat in the face of greater US firepower, or attack like Lilliputians from multiple sides if the US concentrates its forces around the Pakistan border. Further violence and tides of anti-American sentiment could sweep across the region into Pakistan with unpredictable results.

Michael Scheuer, the former CIA official once charged with tracking down Osama bin Laden, suggests that the American delusion is that "by establishing a minority-dominated semisecular, pro-Indian government [in Kabul], we would neither threaten the identity nor raise the ire of the Pashtun tribes nor endanger Pakistan's national security." Scheuer wrote this year that "for the United States, the war in Afghanistan has been lost. By failing to recognize that the only achievable US mission in Afghanistan was to destroy the Taliban and al-Qaeda and their leaders and get out, Washington is now faced with fighting a protracted and growing insurgency. The only upside of this coming defeat is that it is a debacle of our own making. We are not being defeated by our enemies; we are in the midst of defeating ourselves." [Marching Toward Hell, 2008]

The beginning of an alternative may require unfreezing American diplomacy towards Iran and considering a "grand bargain" instead. Teheran is the single power, according to CIA director Deutch, who could destabilize the US withdrawal from Iraq. It happens that they were America's ally against Afghanistan not so long ago. The Iranians have lost thousands of police and soldiers themselves in a border war against Afghan drug lords. According to William Polk, "ironically, the only effective deterrent to the trade is Iran." [Violent Politics, 2008] In exchange for security guarantees against a US-directed regime change, Iran may be willing to discuss cooperation with the "Great Satan" to stabilize its borders with Iraq and Afghanistan. Improbable? That depends on whether one thinks the alternative is unthinkable.

The great reappraisal might be underway. In December 2008, Lawrence Korb and Laura Conley of the Center for American Progress published an op-ed piece calling for US-Iran talks over Afghanistan. The CAP is headed by John Podesta, senior official in the Obama transition.

Since twists and turns seem to be the only pattern in divide-and-conquer strategies, it is possible that Obama thinks being tough towards Afghanistan and Pakistan is a defensive cover for withdrawing from Iraq, and he will follow up with unspecified diplomacy after he takes office. But history shows that creeping escalations create a momentum and constituency of their own. Obama might get lucky, lower the level of the visible wars, and embrace a diplomatic offensive. But North and South Waziristan could be his Bay of Pigs.

How can this war be opposed effectively? If Obama appears to be negotiating a diplomatic solution with some success, he will enjoy wide support within the media and Congress. If the additional 20-30,000 American troops appear to be "stabilizing" the situation, public criticism may be modest in scale. But there is widespread, if latent, public opposition to anything resembling an occupation or quagmire in Afghanistan-Pakistan, especially with the American economy in dire straights. The time is coming when these will be known as Obama's wars, and seen as an unproductive distraction from his main mission as president. The deployment of top journalists like the Times' Dexter Filkins to the Afghan front already has increased the quality of press coverage. International protest is certain to grow, given official reservations already expressed by governments in Germany, Italy, Spain and Poland over civilian casualties, air strikes, human rights violations and counter-narcotics missions. The massive human rights violations in Afghanistan will also begin to produce a round of worldwide condemnation. An international anti-war movement is on the horizon.

The cost of Afghanistan will be seen as unsustainable as well; the $36 billion for annual military operations is certain to climb, while the $11 billion spent since 2002 on non-military development cannot begin to address the country's problems. Whether Obama can afford guns-and-butter in Afghanistan as America's own infrastructure and social services fall apart is a question that could move to action "cities for peace"campaigners, health care advocates, Iraq veterans and military families, among many others. And if these wars continue through Obama's first term, a great moral discontent will grow among many Americans who voted for peace in 2006 and 2008.

Tom Hayden is the author of Ending the War in Iraq [2007], The Voices of the Chicago Eight [2008], and Writings for a Democratic Society, the Tom Hayden Reader [2008].